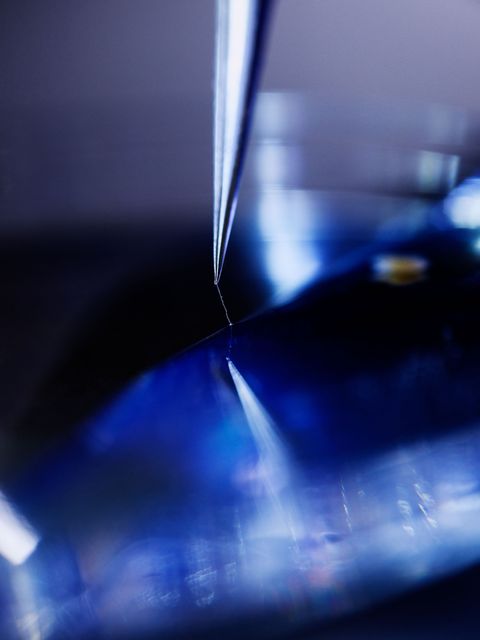

On a Saturday morning in a research lab at Cal State Fullerton, Andy Galpin, Ph.D., C.S.C.S.*D., approaches my left quadriceps with a hollow-point needle designed to extract a chunk of muscle tissue. The sensation, he tells me, “will feel like a biopsy.” Since I’ve never had a biopsy, telling me the procedure feels like itself is like saying moose tastes like moose; the information is illuminating only if you’re really into ungulate meat. But Galpin, who estimates that he’s been on the sharp end of 40 biopsies over the past dozen years or so, says there’s really no other way to describe it. He’s an associate professor at the Center for Sports Performance at Fullerton and has skin (and flesh) in this game.

For the first few seconds, as Galpin plunges the surgical equivalent of a post-hole digger into my thigh, it feels like a grade-school bully pressing his knuckle into my leg. Then the sensation shifts into reverse as he pulls out. A grad student bandages the quarter-inch hole while Galpin transfers the excised piece of my vastus lateralis muscle from the needle to a petri dish. I see the sample up close a few minutes later: four parallel strips of tissue, each perhaps a centimeter long and a millimeter wide. Under a microscope they look like four tuna steaks. Galpin estimates that each microfillet contains at least 500 individual fibers. But they won’t look appetizing for long. After stewing for a week in a special juice called “skinning solution,” the color will disappear, and Galpin will be able to pull single fibers from the translucent mass.

That’s when I’ll learn what I’m made of… or at least what my quads are made of. And that matters for two reasons: first, because the quadriceps muscles are among the body’s biggest, involved in everything from running and jumping to getting up from a chair; second, because leg extension strength, a function of the quads, is frequently tested and may predict your risk of early death from any cause. The combination of fibers in those crucial muscles says a lot about how fit you are now and what you’ll have to worry about down the road.

What You Need to Know About Muscle Fibers

Until recently, scientists thought there were three types of muscle fibers: type I (slow twitch), type IIa (fast twitch), and type IIx (super fast twitch). They also thought the distribution was fixed. So a marathon champion with 90 percent slow-twitch fibers in his thighs was born with this inherent advantage, same as a world-class printer with a predominance of fast-twitch ones.

With new innovations—faster separation techniques and more powerful microscopes—we’ve learned that muscle fibers are actually a continuum of six types, ranging from slow to fast. Even the word “type” is outdated. The new nomenclature is “myosin heavy chain,” or MHC. (Myosin is the component of muscle fibers that initiates a contraction.) Slower-twitch fibers contain more mitochondria, the cell parts that generate energy; they’re also capable of using more fat for energy. Faster-twitch fibers burn glycogen; they can fatigue within minutes of exertion.

An untrained, genetically average guy might have some 40 percent MHC I, 30 percent MHC IIa, and 30 percent hybrid fibers, which are either a combination of slow and fast (I/IIa), fast and superfast (IIa/IIx), or all three (I/IIa/IIx). Those hybrids, Galpin says, “are sitting in the middle saying, ‘You’re not really doing anything, so I’m just going to float to this nebulous spot until you give me something I need to be.’”

When you commit to a lifting program, many of those hybrids will transition to fast-twitch. It starts within weeks, and in the first year of training, as many as 20percent could change into fast-twitch fibers, increasing your strength and power. With endurance training, the hybrids go the other direction, toward MHC I. There’s no right or wrong or even ideal mix of fiber types; your muscle cells adapt to what you need them to do. Conversely, if you work out for a while and then stop, your well-trained slow- and fast-twitch fibers quickly revert to hybrids, in effect going to the sidelines to wait for their next assignment. Research on astronauts reveals that these kinds of changes can happen in just 11 days in space.

Twin Muscle Plasticity

Galpin’s research has distinguished lineage. It began at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden (the place that chooses the Nobel Prize winner in physiology), wherein 1959 the percutaneous muscle biopsy was modernized. A professor at Ball State University traveled there to learn the technique, and he in turn taught it to Galpin and Jimmy Bagley, Ph.D., a colleague of Galpin’s, when they were earning their doctorates. Now Galpin and Bagley are taking the research a step further by looking at the structure and function of muscle fibers in people ranging from elite strength and power athletes to end-stage kidney failure patients.

Between those extremes are Paul and PeteMcLeland, 54-year-old identical twins with completely different fitness habits. They gave Galpin and Bagley a remarkable case study showing how fiber types can change over a lifetime. Paul, a high school teacher and track and cross-country coach near Chicago, has been a dedicated runner most of his life. In college he was all-conference in cross-country, and at times as an adult he’s gone years without missing a single day of training. “I’m a plugger, grinding for each mile and minute,” he says.

Pete, who notes that he’s three minutes older than his brother, always preferred cycling and has biked across the country multiple times. But due to long hours at his sales job and a debilitating ankle injury 12 years ago, he no longer has a regular fitness routine. Their health and fitness profiles are predictable: Paul weighs less and has a lower resting heart rate. His blood work shows lower cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood sugar. But Pete has just as much muscle mass as his brother and smoked him on tests of leg and grip strength. Their muscle fiber biopsies reveal very different adaptations due to their fitness regimens. Paul’s muscles adapted to match his singular pursuit, while Pete’s inactivity resulted in still having 25 percent of hybrids unassigned. The takeaway, Galpin says, is the amazing plasticity of human muscle: “With enough time and enough exposure, you have no boundaries.”

While Galpin’s research indicates that major shifts in fiber type (around 25 percent) are possible, it’s the minor shifts (around 10 percent, from fast to slow or vice versa) that are more common, says Kevin Murach, Ph.D., an exercise scientist at the University of Kentucky. “We have a pretty good handle on what type of stimulus elicits a certain kind of switch, but the precise molecular details are elusive. It’s likely not just one thing but a combination of things that causes fiber-type transitioning.” Another open question is the degree to which genetic pre-disposition plays a role.

How the Research Affects You

Eventually, Galpin says, coaches may be able to design programs based on an athlete’s specific fiber type mix, or even create programs to change the mix to one more favorable for his sport. He’s already experimenting with a slimmer needle and works with pro athletes doing muscle fiber screening to see if they’re training at peak efficiency. “Instead of just guessing at programming, we can say, ‘Yep, this is your issue. Your slow-twitch fibers are garbage.’”

Those applications still aren’t available to the public, but in the meantime there are ways you can gauge the effectiveness of your workouts. If you’re a rookie or coming back after a layoff, ask yourself: Are you gaining strength and/or speed? Are you increasing your volume—more sets and reps, more intervals, longer sessions? If you’re more experienced: Are you maintaining or hitting new maxes for a variety of different lifts and/or maintaining speed at peak levels? Are you maintaining your overall volume of exercise?

“I love these studies because the endpoint is death—the ones who are stronger tend to live longer.”

Galpin himself is a bit of a hybrid. At 34, with a compact, wide-shouldered frame, he still looks like the jock he started out as—a small-town kid from Rochester, Washington, who played football at Linfield College, a Division III powerhouse in McMinnville, Oregon, where he won a national championship in 2004. But he paid a big price for glory: Five surgeries on his right knee left him with limited ability to jump, sprint, squat, or do Olympic lifts with a full range of motion.“My overall fitness is better for it,” he says. “It’s day-by-day to see what works and what doesn’t work, which forces me to be creative.”

His creativity leads him in many directions. In addition to his research, he practices Brazilian jiu-jitsu and trains high-level athletes in combat sports (wrestling, boxing, MMA), football, and baseball. He hosts the Body of Knowledge podcast series, combining stories about the history of exercise science with insights into the latest research. He’s also coauthored a book titled Unplugged, which advocates using less technology in your life and workouts and trusting your body more.

The book only sounds like it contradicts his research. In truth, the more time Galpin spends looking at muscles under a microscope, the more he appreciates how crucial they are to all the things we enjoy in life and to how many years we get to use them. To Galpin, health and fitness are simple, straightforward pursuits. “If you look at what predicts mortality—and I love these studies because the endpoint is death—the ones who are stronger tend to live longer.”

But strength isn’t the only fitness parameter linked to longevity. Cardiorespiratory fitness is also associated with longer life. So is more total physical activity. The research is unambiguous enough, but the message can get garbled by experts who, despite their generally good intentions, are stuck in fitness silos. They’re so invested in strength or endurance training that they’re blinded to the value of everything else.

Most doctors and fitness experts will tell you to start with sustained effort—walking, especially. That’s led to the goal of 10,000 steps a day. That’s good, but you shouldn’t stop there. “Strength is a major part of health,” Galpin says. “The more strength you gain, the more you’ll move around during the day.” Stronger muscles allow your heart to do its job with less effort, making it easier to do everything from walking and climbing stairs to lift-ing and carrying bags of groceries or sacks of dog food. “I mean, what dissuades you from doing those random acts of physical activity? It’s not all cardiovascular function. It’s also being weak!”

Galpin’s prescription: Do a few things involving heavy weight. Do a few things that get your heart rate up. Do a few things that require sustained effort. “It’s not sexy, but all the research shows that those three things are the most important,” he says. If you workout just three times a week, Galpin recommends this program:

If you want to do a fourth session, your best bet is another weight workout, but using moderate weight with the goal of building muscle.

Research Results and Workout

Two days after my biopsy, we sit in a basement room at San Francisco State University, where Bagley operates a laser confocal microscope, a half-million-dollar piece of amazeballs technology. It lets exercise scientists look at individual muscle cells with a degree of three-dimensional precision unheard of until recently. Today we’re comparing two cells: The first is from a young, athletic woman. The second is from an elderly kidney failure patient who’s participating in a study Galpin and Bagley are working on.

The difference is striking. While the nuclei of the healthy person are neatly positioned and uniformly shaped, those of the unhealthy one look like the floor of a college dorm room, littered with random piles of dirty clothes. It matters because the nuclei hold your DNA. That means they control the growth and repair processes. If they can’t repair a fiber, it dies. “And dead fibers don’t come back,” Galpin says.

We don’t know which came first, the failing organs or the dying muscle cells. But we do know that in almost every case, daily choices can add up to profoundly different outcomes.“Your lifestyle has more of an influence on how your muscle acts and behaves than we’ve ever really thought,” Galpin says. “Even if you’re born with shitty genetics, you can train your way out of a lot of that.” That’s true for all of us, at every age.

That’s on my mind when I receive the results of my fiber analysis 10 days after I return from California. It’s worse than I feared. I have 38 percent hybrid fibers—those guys sitting on the sidelines waiting to turn into something specific—and just 12 percent MHC IIa, the ones responsible for strength and power. “Considering your age [I’m 60], it’s not that terrible,” Galpin says. But, just in case I don’t get the point, he adds, “It’s not amazing either.”

There was no risk of me not understanding, not after immersing myself in Galpin’s world and seeing what happens when good cells go bad. Despite chronically sore knees, I need to get those fast-twitch bastards off the bench and back into the ballgame.

That’s why the next day I found myself using the leg extension machine for the first time in probably 20 years. To my surprise, by shortening the range of motion at the bottom, I could work my quads to a deep level of fatigue with no discomfort at all. The same proved true with the leg press, another machine I’ve rarely used in recent years. Over time, if I keep pushing myself, I should get some of my IIa back.

The second part of my comeback strategy is conditioning. I’ve been doing intervals, carries, and sled work, but it’s clear that I need to do a lot more. My biopsy showed 50 percent MHC I fibers, which is probably my low-training setting. Getting a few of my slow-fast hybrids to join the slow side will give the muscles better endurance, and allow them to use more fat for energy.

In the past I could come up with any number of reasons to avoid or truncate the areas of fitness training I didn’t enjoy. But now that I’ve seen what’s inside my muscles, I realize I have no good excuses.

Source: Read Full Article