It is an open question to what extent protection against reinfection persists after overcoming a SARS-CoV-2 infection. The “Rhineland Study”, a population-based study conducted by DZNE in the Bonn area, is now providing new findings in this regard. Blood samples taken last year indicate that an important component of immunity—the levels of specific neutralizing antibodies against the coronavirus—had dropped in most of the study participants with a previous infection after four to five months. In some, antibody titers even fell below the detection limit. These results, published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, lay the groundwork for planned follow-up studies.

Between April and June 2020, around 5,300 adult Bonn residents were tested for antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus as part of the “Rhineland Study”—an ongoing DZNE study investigating population health. For this purpose, blood samples were taken and analyzed. If initial results were positive, these samples were subjected to further testing by means of a so-called “plaque reduction neutralization test” to ensure that the detected antibodies were specifically directed against SARS-CoV-2—and not against other coronaviruses that, e.g., can trigger common colds. In these analyses, the team of the Rhineland Study cooperated with the Institute of Virology at the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Waning Antibodies

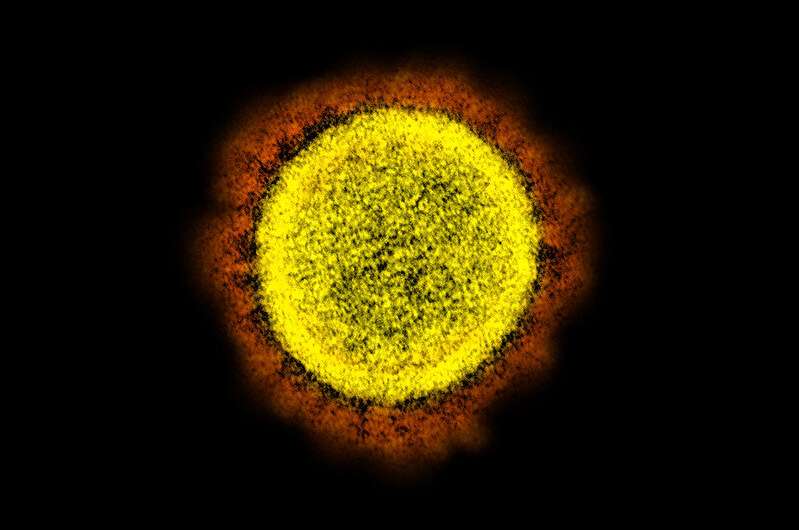

Antibodies are proteins produced by the immune system with which the human organism defends itself against pathogens. In 22 study participants, “neutralizing” and thus particularly effective antibodies, which directly prevent the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells, could be detected. This indicated previous contact with the virus. The majority of these individuals reported to have experienced only a mild or even asymptomatic course of the disease. They were retested in September 2020—approximately four to five months after the initial blood sampling. In most of these persons antibody levels had waned, and in four individuals antibodies could not even be detected anymore.

“These studies occurred during the first wave of the pandemic. The number of people who had already become infected at that time was therefore relatively low. In the meantime, we have a different situation,” Prof. Monique Breteler, head of the Rhineland Study, says. “Nonetheless, our results suggest that the widely used, just single-stage procedure for detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies by immunoassay is insufficient to reliably identify a passed infection. In any case, in our sample, only about one-third of the individuals who were positive by immunoassay actually had specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. This should be considered in immunity studies. In my view, a multistage testing procedure like the one we used is highly recommended.”

Duration of immunity against SARS-CoV-2

These study data, however, do not allow direct inferences about the extent to which the waning of the antibodies affects the immune response, Dr. Ahmad Aziz, DZNE scientist and first author of the current publication, notes. “The decrease in antibodies seems to happen relatively quickly. However, the immune system has other tools to fight off pathogens. Antibodies are without doubt relevant, but they are only part of a larger arsenal. Other studies suggest that another component, which we call the cellular immune response, may persist despite dropping antibody levels.”

In fact, little is known about the durability of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 after infection. This may also depend on the particular variant of the virus. “On the part of the Rhineland Study, we intend to continue to track the development of the pandemic and its effects on the mental and physical health of the population. Our study is the basis for this.” Breteler says. “Ultimately, we want to help better understand why some people don’t even notice an infection and others become severely ill.”

Source: Read Full Article