University of Leeds researchers found a concerning lack of robust data for non-white European women in previous studies examining the impact of diet on gestational diabetes.

Their findings stress the need for culturally appropriate research methods to accurately understand the contribution of healthy or unhealthy diets on developing and managing diabetes during pregnancy across all ethnicities.

Only then can the effectiveness of current prevention strategies be accurately tested and tailored to be culturally appropriate and effective.

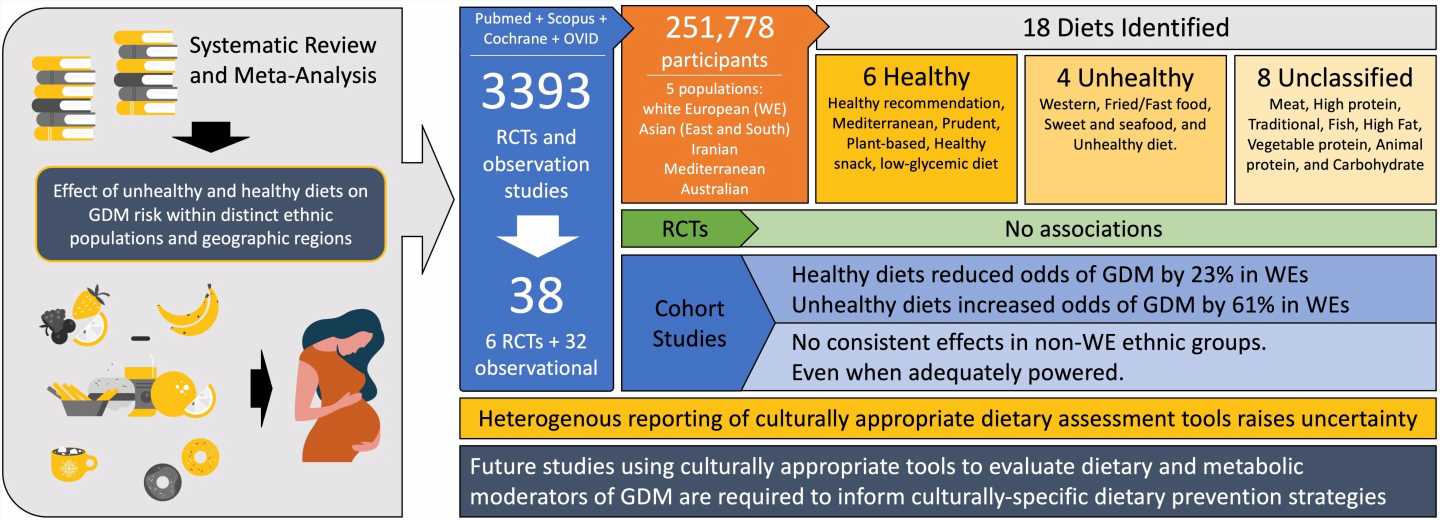

The paper, published in PLOS Global Public Health, systematically assessed 34 previous studies, which matched their strict criteria. Despite numerous significant associations between dietary patterns and gestational diabetes in white European women, the team were unable to draw a firm conclusion on the ability of diet to mitigate gestational diabetes in women from other ethnic groups.

Study first author Harriett Fuller a Ph.D. researcher in the School of Food Science and Nutrition said: “The results offered reassuring confirmation that common dietary strategies, such a cutting down on carbohydrates and sugar, are proving successful in preventing gestational diabetes in white European women.

“We cannot say with confidence that these common dietary prevention strategies are—or are not—having the same effect on other ethnic groups. Currently, the data simply doesn’t exist to confidently answer this question and that is, frankly, incredibly disappointing.”

Globally, one in seven pregnant women are diagnosed with gestational diabetes, which is associated with numerous health risks to both mother and child.

Previous studies have shown that women from ethnic minority groups, such as African and Asian groups, disproportionally suffer from gestational diabetes compared to white European women, largely independent of country of residence or general health.

This suggests that underlying features and characteristics unique to ethnic minority groups and their cultures are driving gestational diabetes risk disparity, and positions ethnicity as a major disease determinant.

Principal investigator Dr. Michael Zulyniak, a lecturer in obesity at Leeds said: “There is an urgent need for dietary advice to inform global health strategies. But without robust data to support tailored guidance, national gestational diabetes prevention strategies are often biased towards evidence from white European centric studies.

“This could be causing a serious gap in helpful prenatal and antenatal advice.”

Out of the 3,393 studies identified, 38 publications provided information on five population groups: white European, Asian, Iranian, Mediterranean and Australian and were included in the team’s meta-analysis.

From those, of six randomized controlled trials included in the review, five studied non-white European populations. Of these, only three considered culturally appropriate research tools.

Of 32 observational studies identified, the authors found a high variability in patterns of food intake between ethnic groups—possibly due to a misunderstanding of ethnic-specific food preferences, cooking methods, and nutritional composition.

Co-author Dr. Bernadette Moore said: “We want to stress that our findings do not negate the importance of diet both before and during pregnancy. No matter your ethnic group the benefits of a healthy balanced diet are wide-ranging even beyond pregnancy care.

Source: Read Full Article