.jpg) Thought LeadersSamuel Norman-HaignereAssistant ProfessorUniversity of Rochester Medical Center

Thought LeadersSamuel Norman-HaignereAssistant ProfessorUniversity of Rochester Medical CenterIn this interview, News-Medical speaks to Samuel Norman-Haignere about his latest research that discovered a neuronal subpopulation that responds specifically to song.

Please can you introduce yourself, tell us about your background in neuroscience, and what inspired your latest research into the neural representation of music?

I’m an Assistant Professor at the University of Rochester. I am starting up a lab to study the neural and computational basis of auditory perception. We develop computational methods to reveal underlying structure from neural responses to natural sounds like speech and music, and then develop models to try and predict those responses and link them with human perception.

This recent study was a follow-up to a prior study where we measured responses to natural sounds (speech, music, animal calls, mechanical sounds, etc.) with fMRI. In that study, we inferred that there were distinct neural populations in the higher-order human auditory cortex that respond selectively to speech and music, but we weren’t able to see how representations of speech and music were organized within these neural populations.

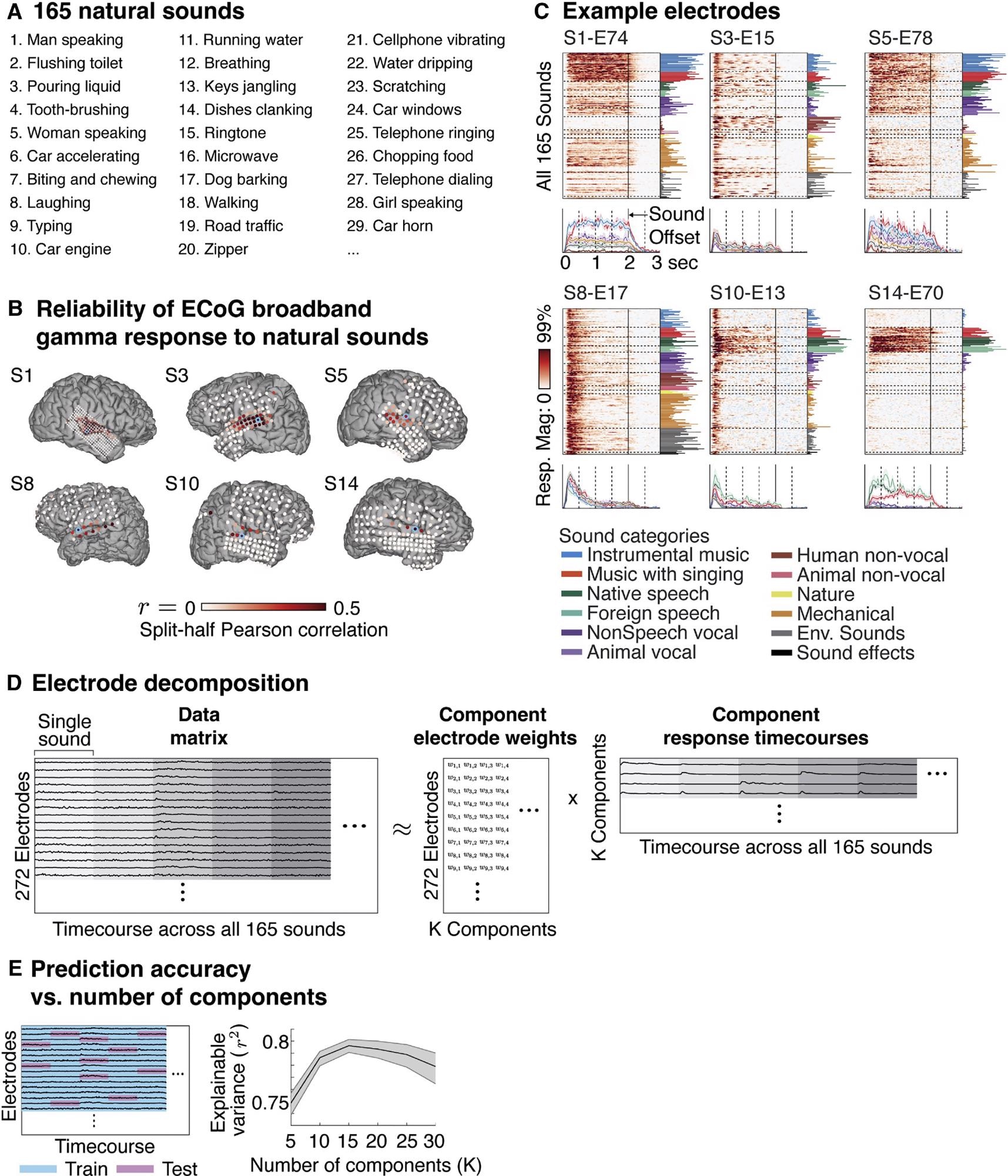

To address this question, we performed the same experiment but instead measured responses intracranially from patients with electrodes implanted in their brain to localize epileptic seizure foci. These types of recordings provide much higher spatiotemporal precision, which was important to uncovering song selectivity.

How did you investigate the neural representation of music and natural sounds?

We measured neural responses to natural sounds using both intracranial recordings from epilepsy patients as well as functional magnetic resonance imaging. We then used a statistical algorithm to infer a small number of canonical response patterns that collectively explained the intracranial data, and we mapped their spatial distribution with fMRI.

Image Credit: A neural population selective for song in human auditory cortex

Your investigation found a novel key finding. What was this finding, and how does it change the way we think about the organization of the auditory complex?

Our key novel finding is that there is a distinct neural population that responds selectively to singing. This suggests that representations of music are fractionated into subpopulations that respond selectively to particular types of music.

How may the new statistical method developed in this study allow for further investigation in the field?

The statistical method is broadly applicable to understanding brain organization using responses to complex natural stimuli, like speech and music.

The method provides a way to infer a small number of neuronal subpopulations that collectively explain a large dataset of responses to natural stimuli. This makes it possible to infer new kinds of selectivity you might not think to look for (song selectivity is a great example), as well as to disentangle spatially or temporally overlapping neuronal populations.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging or functional MRI (fMRI) has been used in previous studies to investigate the music-selective component. What advantages did ECoG, or electrocorticography, provide over fMRI that allowed for your novel finding?

ECoG provides much higher spatiotemporal precision, which we showed was important for detecting song selectivity.

With music therapy gaining popularity, especially for dementia patients, how may your findings help understand the link between music, memories, and emotion?

The ability to localize neural populations that respond specifically to music and song might make it possible to better understand how they interact with other regions involved in the perception of memory and emotion.

Image Credit: Kzenon/Shutterstock.com

What do your findings tell us more broadly about the universality of song and how such a component may have evolved?

Song selectivity could reflect a privileged role for singing in the evolution of music. It could also reflect the fact that singing is pervasive and salient in the environment. We really don’t know at this point.

What’s next for you and your research?

Our lab has a variety of methodological and scientific interests all focused on understanding the neural computations that underpin hearing. We are interested in trying to understand what aspects of singing are being coded in the song-selective neuronal population.

We are developing better methods to reveal underlying structure from complex datasets, as well as developing computational models that can better predict the responses that we measure in the higher-order auditory cortex. Our lab also has a significant interest in understanding how the auditory cortex analyzes sounds at different timescales.

Where can readers find more information?

Folks can check my lab website: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/labs/computational-neuroscience-audition.aspx

About Samuel Norman-Haignere

Dr. Norman-Haignere is a cognitive computational neuroscientist, studying how the human brain perceives and understands natural sounds like speech and music. He completed undergraduate studies at Yale and doctoral work at MIT (advisors: Josh McDermott & Nancy Kanwisher). He then completed two postdocs at École Normale Supérieure (advisor: Shihab Shamma) and Columbia University (advisor: Nima Mesgarani), before joining the faculty at the University of Rochester.

.jpg)

His research develops computational and experimental methods to understand the representation of complex, natural stimuli in the human brain and applies these methods to understand the neural and computational mechanisms that underlie human hearing.

Posted in: Thought Leaders | Medical Science News | Medical Research News

Tags: Auditory Cortex, Brain, Cortex, Dementia, Epilepsy, Epileptic Seizure, Evolution, Functional MRI, Imaging, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Music Therapy, Neuroscience, Research, Seizure, Singing, Speech

.png)

Written by

Emily Henderson

During her time at AZoNetwork, Emily has interviewed over 200 leading experts in all areas of science and healthcare including the World Health Organization and the United Nations. She loves being at the forefront of exciting new research and sharing science stories with thought leaders all over the world.

Source: Read Full Article