Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) or cold knife conization of the cervix (CKC) is the standard of care approach for women with cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN 3) because it achieves both disease control and diagnostic evaluation to rule out invasive carcinoma. While both techniques are associated with equivalent efficacy in disease control, each has its virtues and advantages, and clinical judgment is necessary when choosing a technique.1

LEEP, or large loop electrosurgical excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) involves use of electrosurgical current directed through wire loops to excise pieces of cervical tissue. The equipment for this technique is widely available and this procedure can most often be performed safely and comfortably in an outpatient office setting, making it a cost-effective strategy.

Its ease of access means that it can be employed in “see-and-treat” programs where there is concern regarding follow-up. The loop from the device has a tendency to take more shallow pieces of tissue, preserving more cervical stroma. This may be why LEEP has been associated with decreased risk for obstetric complications associated with cervical insufficiency when compared with CKC.2,3

The shallowness and standardized, preset shapes of the loops present challenges with this technique. It can be more difficult to tailor the shape of the excision for particular lesions, and surgeons may need to add a second “top hat” endocervical LEEP after the first ectocervical excision to adequately excise the endocervical canal.

If the “coagulation” setting is used instead of “blend” or “cut,” excessive drag and resistance can develop during the procedure, which can result in the specimen’s being amputated, fragmented, or interrupted mid-sweep. This can severely limit pathologic interpretation of the specimen. Orienting these multiple fragments for pathology to specify margin status can be limited or impossible. Electrosurgical effect (“thermal effect”) at the margins of the specimen can limit accurate interpretation of adequacy of the excision.

CKC of the cervix is a procedure in which a narrow scalpel (typically an 11-blade) is used to excise the ecto- and endocervical tissues in a cone-shaped specimen that ensures maximal inclusion of ectocervical and endocervical mucosa but minimization of stromal excision. Absence of electrosurgery in the primary excision means that pathologists have clean edges to evaluate for margin status.

Because the shape of the incision is unique for each patient, the surgeon can tailor the shape and extent of the cone to focus on known or suspected areas of disease. It is particularly useful when there is an endocervical lesion, such as in cases of adenocarcinoma in situ and in postmenopausal women whose transformation zone is frequently within the canal. In cases of a distorted, atrophic cervix, or one that is flush with the vagina, a conization procedure in the operating room affords surgeons greater control and precision.

Major limitations of this procedure are that it is typically performed in an operating room setting because of the potential for intraoperative bleeding, and its increased risk for early and late complications. The conization procedure is associated with increased obstetric risk in later pregnancies, possibly because of more significant disturbance of cervical stroma.2,3

As mentioned earlier, both procedures are associated with equivalent outcomes with respect to control of disease.1 CKC procedures are associated with more complications, including bleeding (intraoperatively and postoperatively) than are LEEPs. Traditionally, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) has been preferentially treated with CKC because of the propensity of this lesion to reside within the endocervical canal, a region more readily and extensively sampled with the CKC.

However, provided that the LEEP specimen achieves negative margin status, there is no specific benefit of CKC over LEEP. Guidelines recommend that AIS is excised as a single specimen (without a “top hat”) to achieve accurate pathology regarding margins in the endocervical canal.4 Considering that a specimen depth between 10 and 20 mm is ideal in the setting of AIS, it may be difficult to achieve this depth with a single-pass LEEP depending upon the dimensions of the cervix. It is due to these technical challenges associated with LEEP that CKC is typically preferred in the treatment of AIS.

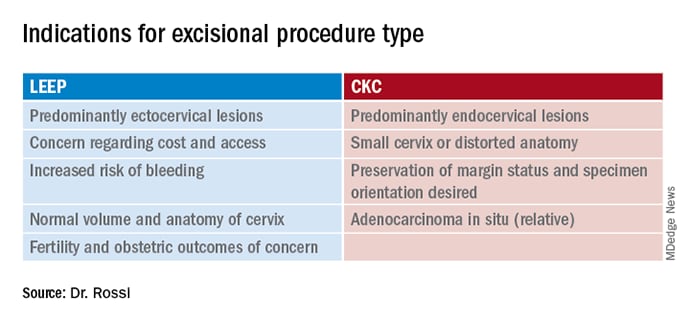

Ultimately, the decision regarding when to choose LEEP versus CKC is nuanced and should be tailored for each patient. Factors to consider include the patient’s ease of follow-up, financial limitations, preexisting distortion of anatomy, and the need to minimize obstetrics risks or achieve wider margins.

For example, a young, nulliparous patient with an ectocervical lesion of squamous dysplasia would likely best be served by a LEEP, which preserves her cervical stroma and affords her easy access and affordability of the procedure. A patient with a bleeding diathesis including iatrogenic anticoagulant therapy may also benefit from a LEEP to achieve better hemostasis and lower risk of bleeding complications.

A postmenopausal woman with a narrow upper vagina and cervix flush with the vagina from prior excisional procedures may benefit from a conization in the operating room where adequate retraction and exposure can minimize the risk of damage to adjacent structures, and the shape and size of the excision can be tailored to the long, narrow segment that is indicated. The table highlights some of the factors to consider when choosing these options.

In summary, LEEP and CKC are both highly effective excisional procedures that can be considered for all patients with cervical dysplasia. Decisions regarding which is preferred for patients are nuanced and should consider individualized anatomic, pathologic, functional and financial implications.

Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no conflicts of interest. Contact her at [email protected].

References:

1. Martin-Hirsch PL et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001318.

2. Arbyn M et al. BMJ. 2008;337:a1284.

3. Jin G et al. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014 Jan;289(1):85-99.

4. Perkins RB et al. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24(2):102.

This article originally appeared on MDedge.com, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Source: Read Full Article