In 1990, His Holiness the Dalai Lama called up Barry Kerzin, MD, for advice.

That may not be as outlandish as it sounds. For 2 years, California native Kerzin had been living in Dharamshala in northern India, on the edge of the Himalayas, providing free medical care to locals including Buddhist lamas. He had met the 14th Dalai Lama before, but they didn’t have a special relationship.

There was a cholera outbreak in Rio de Janeiro, and the Dalai Lama was seeking medical advice on whether he could safely attend an environmental conference there. His Tibetan medicine doctor, Tenzin Choedrak, warned him not to, but Kerzin was optimistic and told the Dalai Lama he should be safe due to his access to clean food, water, and an adequate vaccine.

The Dalai Lama considered his options and then called Kerzin back to administer the shot. That’s when Kerzin thought, uh oh.

“There’s an unwritten law that you never draw blood from a Buddha,” Kerzin says. “Subsequently, I realized it meant that you don’t harm. But as a doctor, when you give an injection, you have to see if there’s any blood in the hub of the syringe, and if so, you’ve got to remove it and put it in a new spot. So, I was pretty nervous. When I [checked], there was no blood, and inside I kind of went ‘phew.'”

A Relationship Begins, Both Medical and Spiritual

That day, after the shot, the Dalai Lama led Kerzin by the hand into an adjacent room filled with semiprecious stones and ancient Buddhist statues. There he walked him in circles while giving a Buddhist history lesson.

He concluded by bestowing Kerzin with two stones: a crystal that Kerzin now keeps on an altar in his room in Dharamshala, and a piece of turquoise that he wears around his neck. Kerzin now recognizes that meeting as the beginning of a teacher-student and doctor-patient relationship that would go on to span three decades and counting.

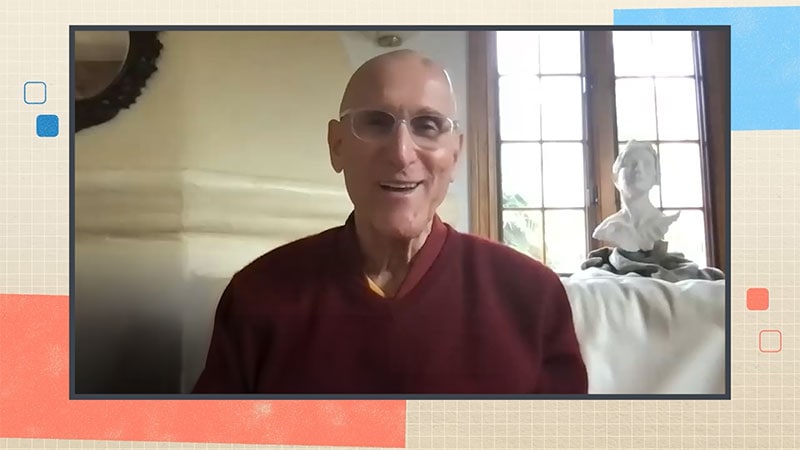

Today, Kerzin is a Tibetan Buddhist monk and one of the Dalai Lama’s personal physicians. He has given lectures on the intersection of Buddhist philosophy and medical science all over the world; founded two educational organizations, the Human Values Institute and the Altruism in Medicine Institute; and offered up his brain for neuroscience research on the effects of meditation.

His concurrent roles as monk and medical doctor give him unique insight into how mindfulness and compassion can help heal the world.

‘What’s My Purpose?’

Kerzin grew up in a liberal Reform Jewish family in southern California. Around the age of 6, he began to ask himself the big questions: “Who am I? What am I doing here? What’s my purpose?”

“Of course, I had no answers,” he says. “I’m not sure I have full answers even now. But those questions were guides for me, though unknown at the time.”

Another defining detail of Kerzin’s life came at age 11 when he developed a subdural abscess, went into a coma, and nearly died. The neurosurgeon who treated him over the next several years became his hero.

Kerzin’s introduction to Buddhism came around the age of 14, when he discovered books by Eastern philosophy scholars D.T. Suzuki and Alan Watts. The impact of these books and his lingering existential questions led him to major in philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley.

After graduation, faced with the choice to pursue a career in academic philosophy or medicine, he remembered his awe of the neurosurgeon who saved his life.

“That was something in my heart,” Kerzin says. “It wasn’t cognitive, intellectual stuff. It was a deep-felt experience. So, my heart won over, and I went into medicine.”

Kerzin earned his medical degree from the University of Southern California and practiced family medicine in Ojai, California, for 7 years.

‘He’s Reading My Mind’

All that time, Kerzin continued studying Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and attended several meditation retreats. The “catapult” into monkhood was a 3-year silent retreat in southern France in the 1980s, during which he shaved his head and donned robes, an experience he likens to “play-acting as a Buddhist monk.”

He moved to Dharamshala in 1988, and not long after their 1990 meeting, Kerzin found himself sitting behind the Dalai Lama as he gave a Kalachakra initiation — a public Buddhist ritual — to around 70,000 people in northern India.

A thought suddenly struck Kerzin, I think he’s reading my mind. At that moment, the Dalai Lama turned around, looked right at him, and smiled before continuing the ritual. He’s really reading my mind! Kerzin thought and, once more, the Dalai Lama turned to look at him with a grin.

“He’s my teacher, and I feel like he’s a father, in a spiritual sense,” Kerzin says. “A lot of the relationship happens not so much on the physical level — it’s more involved with my meditation and feeling his presence.”

Doctor as Student, Teacher as Patient

An aspiring monk needs permission from a lama to be ordained. The first time Kerzin asked, the Dalai Lama sent him away with the instruction to go deeper into his practice. When Kerzin returned 6 months later, he knew he was ready, and the Dalai Lama agreed. His Holiness ordained Kerzin in February 2003.

Today, Kerzin’s relationship with the Dalai Lama revolves around regular medical evaluations, which Kerzin conducts with a small group. But the Dalai Lama’s keen awareness often leaves Kerzin having to remind himself that he’s the doctor, and the Dalai Lama is the patient. “I strongly feel that he takes care of me, that I can’t do anything, really, for him,” Kerzin says. “Of course, that’s not fully true.”

The experience still fills Kerzin with a sense of awe. “To be around [the Dalai Lama] is like being around no other human being I’ve ever been around,” he says. “He’s incredibly compassionate all the time, but that compassion is a little like tough love sometimes. He’s not wishy-washy, he’s not wimpy, he’s not impotent. He’s very powerful and very strong, but it’s the power of love and compassion.”

How Religion and Medicine Mix

Compassion is central to Kerzin’s own mission. In 2015, he founded the Altruism in Medicine Institute, which trains medical professionals in compassion, mindfulness, and resilience to support their emotional health and enhance patient care.

“The practice of medicine is very much [compatible with] being a Buddhist practitioner, because it’s a way of serving,” Kerzin says. “It’s a way to really try to help someone who’s suffering, who’s in pain, who’s sick.”

When he is not working with his two nonprofits or providing medical care for the Dalai Lama and others in Dharamshala, Kerzin teaches. He gives lectures all over the world, shares teachings online twice weekly, and has written four books. He also aims for 10,000 steps a day, meditates at least 2 hours each day — even on long-haul flights — and keeps up with the latest research from major medical journals. The hours he spends meditating on compassion guide him through the rest of his daily responsibilities.

“I don’t get burnout,” he says. “I don’t have a 9-to-5 job, granted, but I do have a very busy schedule. I think the practice of moving beyond empathy to compassion protects us from taking on the pain of the other person, which becomes a main avenue that leads to burnout.”

The Dalai Lama’s Doctor’s Advice to Doctors

Kerzin teaches physicians to create emotional distance from patients’ pain while remaining compassionate and motivated to help.

Kerzin also envisions how compassion and mindfulness might impact the medical industry. He supports systemic changes like longer appointments to help patients feel heard, longer lunch breaks, and dedicated spaces for doctors and staff to sit quietly, away from the noise of technology and chitchat.

Kerzin’s advice for all healthcare professionals is streamlined into the Altruism in Medicine Institute’s AIMIcare app, a collection of meditations, emotional hygiene lessons, and spaces to journal and share thoughts. A key portion of the app focuses on cultivating compassion toward oneself.

“We tend to doubt ourselves a lot, and that makes us more vulnerable,” Kerzin says. “We tend to dwell on the stuff that didn’t go so well and just spiral down. Not that we shouldn’t review that and try to do it better next time, but [we also need] to celebrate the things that went well.”

Following his own advice, Kerzin takes a moment to take in the good stuff. “All in all, it’s the most incredible privilege and honor of my life, and I have goosebumps just talking about it,” he says of working with the Dalai Lama. “I pinch myself, thinking, This must be a dream.”

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and YouTube

Source: Read Full Article