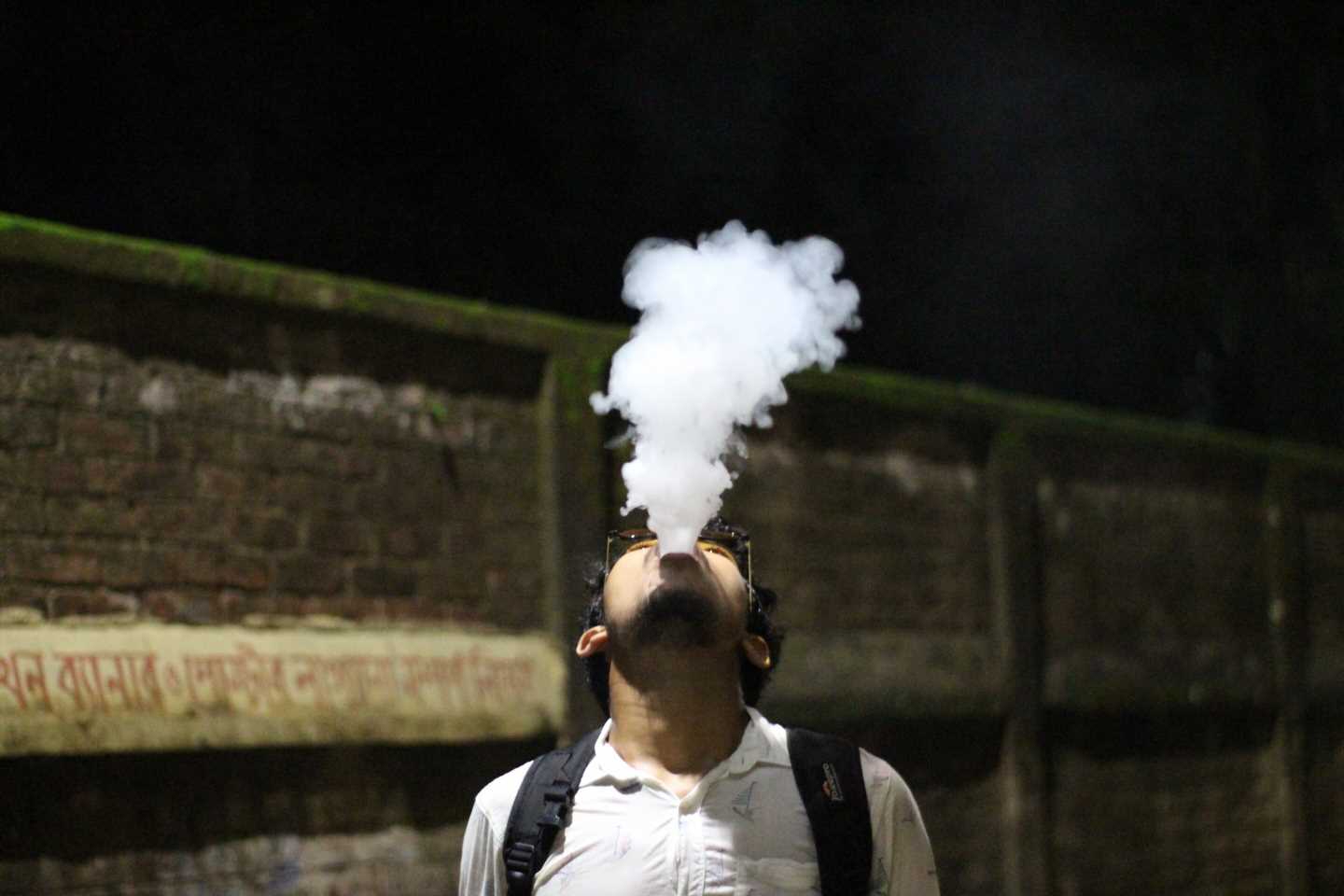

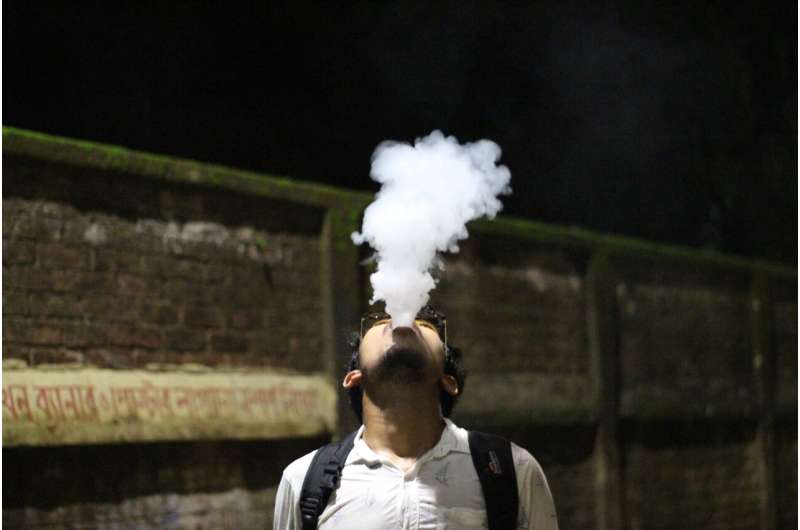

Growing evidence suggests that e-cigarettes may serve as a less harmful alternative to smoking traditional cigarettes, but socioeconomic and racial inequities in cigarette and e-cigarette use are preventing certain populations from reaping these potential health benefits, according to a new study led by Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) and the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California (Keck School of Medicine of USC).

Published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, the study found that Black, Hispanic, and low-socioeconomic status (SES) smokers were less likely to use e-cigarettes as a tool to quit smoking and more likely to believe e-cigarettes are equally or more harmful than cigarettes. These populations are disproportionately affected by smoking-related diseases and health conditions such as cancer and cardiovascular complications, so these misperceptions in vaping risks may prevent e-cigarette uptake as a smoking cessation tool and further exacerbate racial and health disparities in smoking. Cigarette smoking remains the leading preventable cause of disease and death in the US.

“This work highlights the potential unintended consequences of regulations and education campaigns focused solely on communicating the risks of e-cigarettes, without also conveying information about their harm relative to cigarettes,” says study lead author Dr. Alyssa Harlow, an epidemiologist and postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Population and Public Health Sciences at Keck.

Thus, the new findings “highlight the importance of designing public messaging and educational campaigns in a way that effectively communicates both the risks and benefits of using e-cigarettes,” says study senior author Dr. Andrew Stokes, assistant professor of global health at BUSPH.

The study provides new insight into national smoking and e-cigarette trends, using several years of data that reflect the substantial growth in e-cigarette marketing and popularity in the US over the last decade. For the study, Stokes, Harlow, and colleagues from BUSPH analyzed data from the US Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study over five periods between 2013-2019.

The team examined differences in e-cigarette transitions, as well as beliefs and attitudes about vaping harm, by race/ethnicity, income, and education. They divided these assessments among four categories of smoking/vaping behaviors: exclusive smoking; switching from exclusive smoking to exclusive vaping; dual smoking and vaping; and no smoking or vaping.

White adults, as well as those with more education (Bachelor’s degree or higher) and more annual income ($50,000 or more) were more likely to quit smoking and switch to exclusive e-cigarette use after one year, when compared to Black, Hispanic, and lower-SES adults.

Among all people who smoked cigarettes, 69 percent believed that e-cigarettes were equally or more harmful than cigarettes. Hispanic and Black adults were more likely to hold this view of e-cigarette harm, and these perceptions may have contributed to why these populations were less likely to transition from smoking to vaping only.

The researchers say that these sociodemographic differences in cigarette and e-cigarette underscore the need for anti-smoking and vaping policies to consider additional factors beyond youth vaping dangers and e-cigarette health benefits—such as equitable access to e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. While policies that reduce vaping is important, presenting e-cigarettes as more harmful than cigarettes could deter adults who smoke from switching to less harmful forms of nicotine consumption, Stokes and Harlow say.

“Policymakers should consider the impact of e-cigarette regulatory policies on cigarette smoking disparities to promote equitable access to e-cigarettes for cigarette cessation,” Stokes says.

More information:

Alyssa F Harlow et al, Sociodemographic Differences in e-Cigarette Uptake and Perceptions of Harm, American Journal of Preventive Medicine (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.03.009

Journal information:

American Journal of Preventive Medicine

Source: Read Full Article