Jennifer Silva, MD, seeks order where most might find only chaos, and mastery where others might see only baffling complexity.

Whether she’s taming the erratic signals of a heart beating out of rhythm or navigating the circuitous paths of founding a startup company, Silva works to bring logic and clarity to all she does. As a pediatric cardiac electrophysiologist, she cares for young patients whose hearts don’t maintain a proper beat; and as an entrepreneur, she’s developing a technology that she hopes will help doctors like her see the heart in a whole new way — a way that may help them provide better care.

“When someone tells me, ‘That’s too hard,’ that’s going to be the thing I choose to pursue,” said Silva, an associate professor of pediatrics and director of pediatric electrophysiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “I chose to specialize in heart rhythm abnormalities because it was hard, but it simultaneously made sense. There’s a logic to it. There are clear rules and order in what seems to be a chaotic situation, like when the heart beats 300 times per minute, for example. I don’t see the chaos; I see very organized ways to solve the problem. And it can change patients’ lives. The work is very gratifying.”

In kids, like adults, such abnormal heart rhythms can be life-threatening. Eighteen-year-old Chase Jeffrey, one of Silva’s patients, experienced an extremely rapid heartbeat after playing in a high school soccer game three years ago and was diagnosed with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. This congenital heart defect results in an extra electrical pathway between the upper and lower chambers of the heart. The additional circuit can lead to dangerous arrhythmias, and Silva performed catheter ablation procedures to shut it down, as is often done for young athletes at risk of sudden cardiac arrest during high-intensity sports. She hopes the new technology she is developing will help visualize such arrhythmia circuits to make them easier to treat.

Silva, who sees patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, also serves as the School of Medicine’s inaugural faculty fellow in entrepreneurship. Based on her own experience co-founding a startup company called SentiAR, she is providing advice and guidance to colleagues considering their own startup ventures.

“You have to be willing to step outside your comfort zone, to be able to talk to anyone and everyone,” Silva said. “You never know who is going to be able to help you with all the pieces as you move through the process. Our journey started with Washington University’s Office of Technology Management (OTM), which provided training and encouragement throughout the process of applying for a patent. They helped us step-by-step as we crafted the original patent on our ideas.”

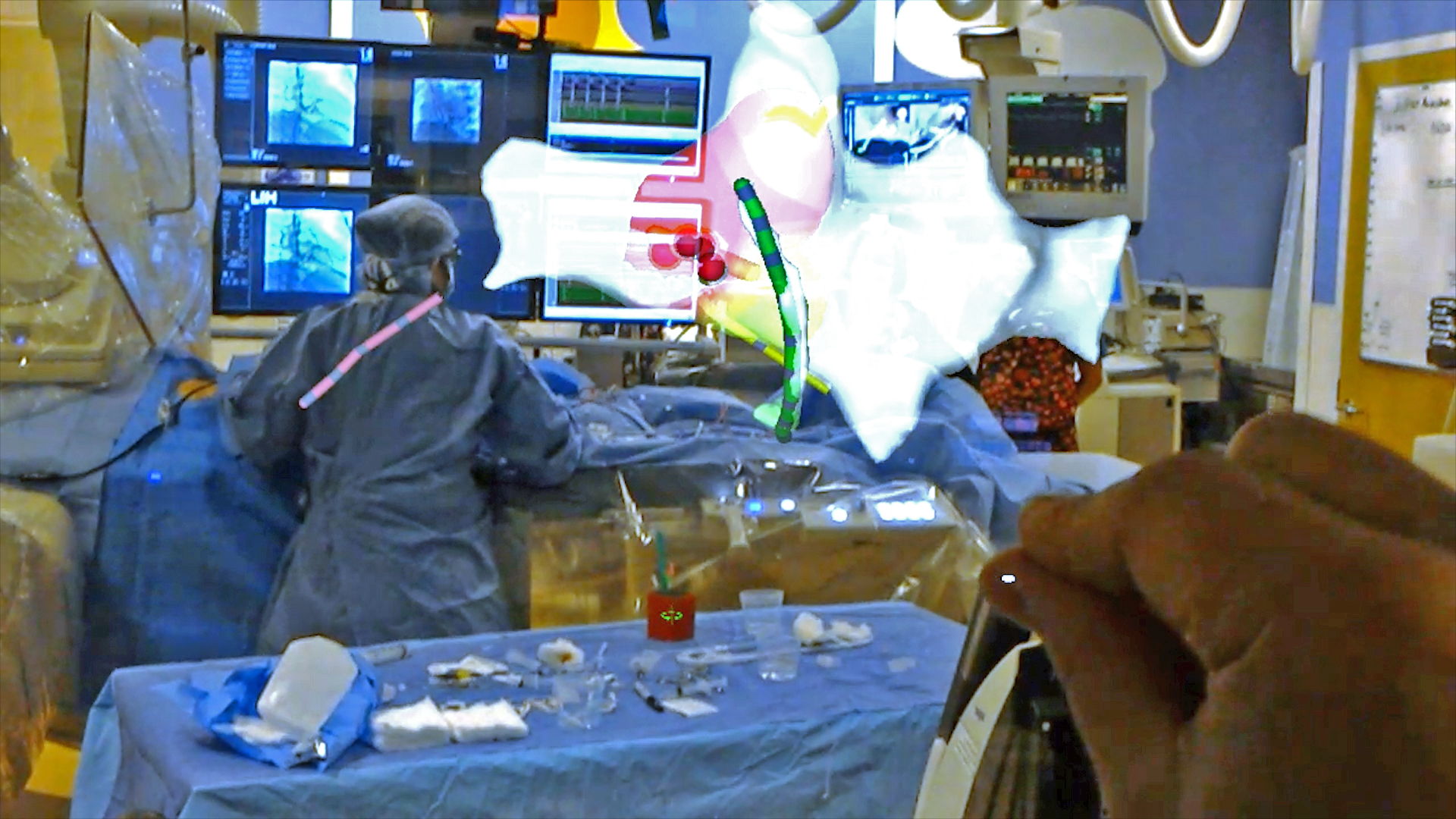

These ideas center around a vision of a 3D heart — beating in real time — floating in mid-air above the patient as an electrophysiologist threads catheters through veins and into the heart to treat the patient’s arrhythmia. The catheters themselves also are visualized in real time on this floating cardiac map, giving everyone wearing specialized headsets the same 3D, real-time model of the patient’s beating heart. The catheters are used to ablate, or burn, tissue that is triggering the heart’s electrical misfires, bringing the rhythm back into proper sync.

As these procedures are performed now, everyone involved with treating the patient is picturing their own 3D map based on live 2D X-ray images. But their 3D mental maps can differ. Jeffrey, the student athlete, for example, needed a second ablation procedure because his arrhythmia returned after the first one. Silva hopes the new technology may reduce the need for second procedures.

“Electrophysiologists need to be very good at mentally overlaying 2D images onto a 3D model that they picture in the mind’s eye,” Silva said. “How do these 2D electrical maps translate into the 3D space inside the heart? Becoming adept at this kind of spatial reasoning takes time and experience, and some people are just inherently better at it than others. We are hoping our 3D visualization technology will help take some of the uncertainty out of this mental mapping.”

To create this 3D virtual hologram of the heart, Silva has partnered with her husband, Jonathan Silva, PhD, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Washington University. His expertise lies in understanding the electrical circuitry of the heart on a molecular level and building mathematical computer models to better understand these circuits and how they can misfire.

“My husband went to a meeting where Microsoft was unveiling new and upcoming technologies, and they were asking the engineers and scientists in attendance how they might use this new augmented-reality technology,” Silva said. “And as an example, they showed a 3-dimensional beating heart. So he called me at home, and we started talking about how we might be able to use it to help the field. I talked with my colleagues in cardiac electrophysiology, and we saw a need for this kind of visualization. These are really important questions for potential academic entrepreneurs to ask themselves. ‘Where are the gaps in my field, and how do I fill them?’”

Silva and her startup company — co-founded with her husband — have partnered with Microsoft to build heart-visualization software that uses the tech giant’s HoloLens headset to create these 3D maps.

Throughout the process of getting the startup running, Silva said it was helpful to be a co-founder of the company and an eventual user of the product. When potential investors had questions about how this might be used and whether there would be demand for the system, she was well-placed to answer those questions. She also spoke a bit about being female in a male-dominated tech startup culture.

“I’m a woman, I’m Indian, I’m an academic,” said Silva, whose parents emigrated to the United States from India before she was born. “I’m not the typical startup founder that investors are accustomed to dealing with. When we first presented our technologies to potential investors, they tended to direct questions to my husband first. And that was OK because he could speak to his part of the project. And I give him credit for always directing people to me when they asked the clinical questions. We all have our unique skill sets that we bring to the team.”

Initially, Silva said they plan to develop the tool strictly as a guidance map for adult and pediatric cardiac catheter ablation procedures. They are on track to apply for approval from the Food and Drug Administration next year. But in the future, Silva hopes they can build elements of control into the device, using it to directly control the catheters inside the patient’s heart.

“The goal is always to provide the best care for the patient,” Silva said. “We’re all here to do a better job because at some point, we’re all patients — our spouses, our parents, our siblings, our kids. Doing better for patients inevitably impacts people we love.”

Source: Read Full Article