Autistic adults have poorer access to appropriate mental health care despite being more likely to experience anxiety or depression than the general population, finds a new study by UCL researchers.

It is estimated that up to 27% of autistic people experience anxiety, and 23% develop depression, compared to 5.9% and 3.3% in the wider population.

Evidence-based psychological therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or counseling, are recommended in by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for autistic people who are struggling with their mental health. However, the researchers wanted to investigate whether the treatments currently available through the NHS are beneficial for the population of autistic people who require them.

The new study, published in Lancet Psychiatry, examined therapy outcomes for 8,761 autistic adults who attended NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression (formerly known as IAPT) services between 2012 and 2019.

NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression is a free NHS service that offers CBT, counseling, and guided self-help, with sessions delivered either face-to-face, individually, in groups, or online.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which considers factors such as a lack of interest in doing things, issues with sleep, and feelings of low mood.

Symptoms of anxiety were measured using the GAD7 questionnaire, which asks how often a person feels worried, on edge or unable to relax.

Researchers used existing data from large medical records databases to measure participants’ outcomes (depression and anxiety scores) both before and after therapy to see if there was an improvement in symptoms.

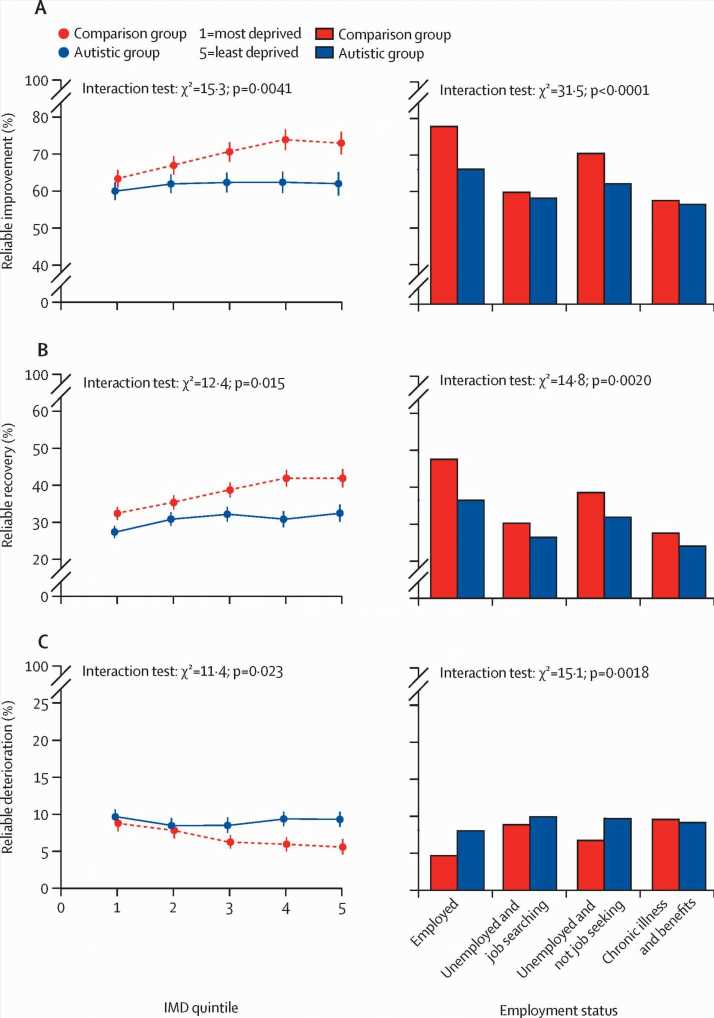

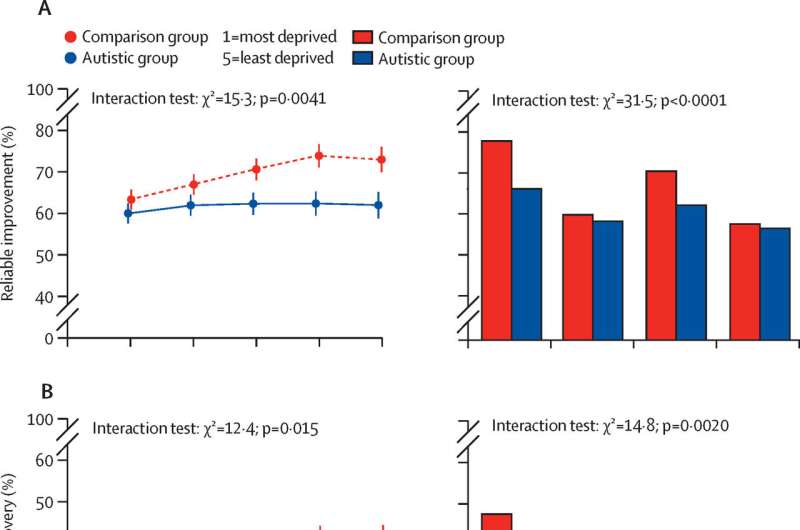

The team found that, on average, autistic adults experienced a decrease in their anxiety and depression symptoms following a course of therapy. However, when these results were compared with the outcomes of nearly two million people who accessed the services but didn’t have a diagnosis of autism in their medical records, researchers found that the outcomes were poorer in the cohort of autistic people.

For example, autistic people were 25% less likely to see an improvement in their symptoms. They were also 34% more likely to experience a deterioration in symptoms of anxiety and depression compared to people in the comparison group.

Lead author, Ph.D. candidate Celine El Baou (UCL Psychology & Language Sciences), said, “Our analysis suggests that therapies offered in primary care may be beneficial for autistic people who experience depression, anxiety, or both. However, we also found that not only were outcomes worse for autistic people following therapy, but the autistic population was largely under-represented in services.”

“While the paper was unable to look at why this might be, we suspect it reflects the specific barriers that autistic people experience to access therapy and the lack of appropriate adaption for neurodiversity, including differences in thinking style, sensory sensitivities or the need for predictability.”

Consequently, the team is now calling for mental health care services to be more accessible for autistic people.

El Baou added, “These findings are important because they highlight how crucial it is to make adequate adaptations to therapies provided in primary care for autistic people and to make them as accessible and effective as possible for them.”

Autism is characterized by specific experiences in social communication and interaction, alongside specialized interests, behaviors, and/or sensory sensitivities.

Many autistic people require adjustments to be made to ensure equal access to health care, employment, and local authority support.

It is estimated that between 1%-3% of the population in the UK are autistic. Although recent UCL research highlights how this figure may be twice as high as previously thought.

El Baou, said, “It is important to note that our analysis has concentrated on those autistic people who have a diagnosis of autism in their medical records. This means that our study cannot tell us anything about therapy outcomes for the vast majority of autistic adults who do not have a formal diagnosis.”

Anoushka Pattenden, Evidence and Research Manager (Partnerships) at the National Autistic Society, said, “We welcome UCL’s new study into the treatment of depression and anxiety experienced by autistic adults and hope to see more studies in this under-researched area.”

“The findings suggest that after treatment, autistic adults are less likely to show improvements in anxiety and depression than others and may actually be more likely to experience a decline in their mental health. This reflects what we hear too often: that autistic adults are not getting the mental health support that they need.”

“Action needs to be taken now to make sure health services are just as effective for autistic people. It’s vital that mental health professionals receive training in identifying and understanding autism, are flexible in their approach, and include autistic people in discussions about the treatment and adjustments they need.”

“We continue to campaign for improved understanding, adapted support, and better outcomes for autistic people to create the fair and equal health system they deserve.”

Study limitations

Trends in the underdiagnosis of autism may mean that the comparison group includes undiagnosed adults.

There is also no way for the study to establish the extent, if any, of adaptations made to clinical practice for autistic adults. Results rely on the assumption that outcomes established in the comparison group are also transferrable to autistic populations. However, while the PHQ-9 has been validated for use in autistic adults, the GAD-7 has not, and recent research suggests that anxiety may present differently in autistic adults.

More information:

Céline El Baou et al, Effectiveness of primary care psychological therapy services for treating depression and anxiety in autistic adults in England: a retrospective, matched, observational cohort study of national health-care records, The Lancet Psychiatry (2023). DOI: 10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00291-2

Journal information:

The Lancet Psychiatry

Source: Read Full Article