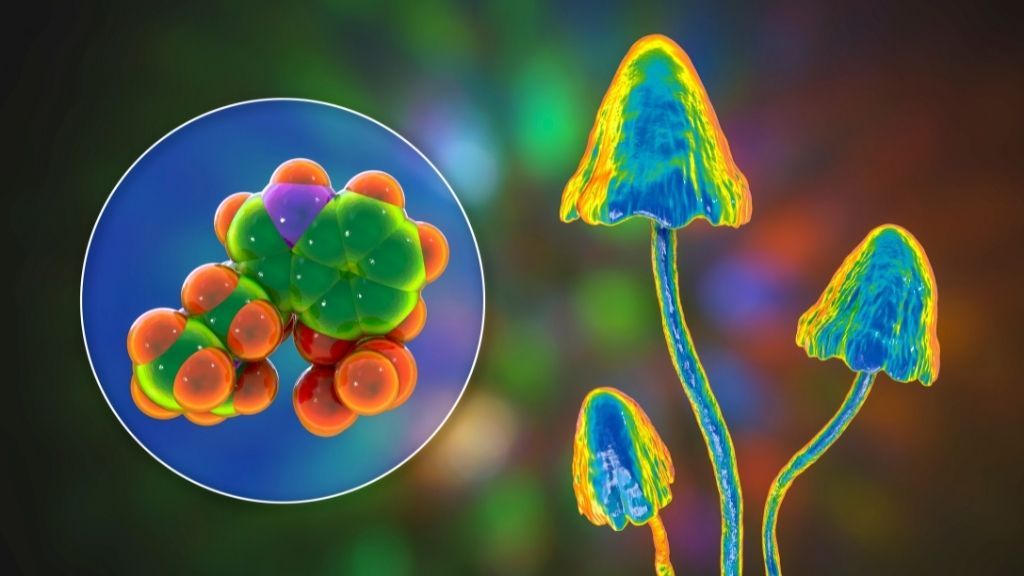

Psilocybin, the hallucinogenic compound found in “magic mushrooms,” could treat depression by creating a hyper-connected brain.

By boosting connectivity between different areas of the brain, the psychedelic may help people with depression break out of rigid, negative patterns of thinking, a new study suggests.

Recent clinical trials have suggested that psilocybin may be an effective treatment for depression, when carefully administered under the supervision of mental health professionals. In the new study, published Monday (April 11) in the journal Nature Medicine (opens in new tab), researchers probed exactly how the psychedelic works to improve peoples’ depressive symptoms. To do so, the team collected brain scans from about 60 patients who had participated in clinical trials for psilocybin therapy; these brain scans revealed distinct changes in the patients’ brain wiring that emerged after they took the drug.

If you or someone you know needs help, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

“We see connectivity between various brain systems increasing dramatically,” first author Richard Daws, who was a doctoral student at Imperial College London at the time of the study, told Live Science. Healthy individuals with high levels of well-being and cognitive function tend to have highly connected brains, studies suggest, but in people with depression, “we sort of see the opposite of that — a brain characterized by segregation,” said Daws, now a postdoctoral research associate at King’s College London. This sort of organization undermines the brain’s ability to dynamically switch between different mental states and patterns of thinking, he said.

The study supports the idea that psilocybin relieves depressive symptoms, at least in part, by boosting connectivity between different brain networks, said Dr. Hewa Artin, the chief resident of outpatient psychiatry at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. That said, “additional studies will be needed to replicate results and validate findings,” Artin told Live Science in an email.

Promising results

The new study included 59 people, 16 of whom participated in one clinical trial for psilocybin and 43 who participated in another.

The first trial included people with treatment-resistant depression, meaning the participants had tried various antidepressants in the past without experiencing improvement. In the trial, these patients initially received a 10-milligram dose of psilocybin, and then seven days later, they received an additional 25-milligram dose. The participants were carefully monitored during each treatment session and spoke with psychotherapists afterward, to reflect on their experiences.

To see how the patients’ brains changed after treatment, the researchers used a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures changes in blood flow to different parts of the brain. The movement of oxygenated blood through the brain reflects which regions of the organ are active through time. The participants underwent fMRI scans prior to the start of therapy and then one day after their 25-milligram dose; and their depressive symptoms were also assessed before and after treatment.

The fMRI scans showed that the patients’ brain networks became less siloed and more integrated with one another following the treatment, as evidenced by the dynamic flow of blood between them. These changes correlated with long-term improvements in the patients’ depressive symptoms.

The second trial differed from the first in that it was a “randomized controlled trial,” considered the gold-standard form of clinical trial. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either psilocybin or the conventional antidepressant escitalopram (Lexapro); neither the participants nor researchers knew which medication was given to which participant.

The psilocybin group received two 25-milligram doses of the psychedelic, spaced three weeks apart, and also took sugar pills throughout the trial. The escitalopram group received two 1-milligram doses of psilocybin, also spaced three weeks apart, and took daily escitalopram pills throughout the trial.

The 1-milligram doses of psilocybin would not be expected to have any appreciable psychedelic effect, so they served as a placebo, senior author Robin Carhart-Harris, who was the head of the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London at the time of the study, told Live Science. It would usually take a dose three to five times that amount to generate an effect, said Carhart-Harris, who is now director of the Psychedelics Division within Neuroscape, the University of California, San Francisco’s translational neuroscience center.

The escitalopram group showed no significant changes in brain connectivity after treatment, but as in the first trial, those who took psilocybin showed marked increases in brain network integration. And notably, patients in the psilocybin group experienced “significantly greater” improvements in their depressive symptoms than those who took escitalopram.

“That’s very important, because it sort of suggests that psilocybin’s antidepressant effect works via a different mechanism to the way that sort of conventional antidepressants work,” Daws said.

—’Trippy’ bacteria engineered to brew ‘magic mushroom’ hallucinogen

—’Magic mushrooms’ grow in man’s blood after injection with shroom tea

—A ‘pacemaker’ for brain activity helped woman emerge from severe depression

What is that mechanism? It likely involves a structure on brain cells known as a serotonin 2A receptor, Carhart-Harris said.

Like LSD and other psychedelics, psilocybin plugs into serotonin 2A receptors in the brain and activates them. These receptors appear in particularly high quantities in specific regions of the wrinkled cerebral cortex that are involved in high-level cognitive functions like introspection and executive functioning, Carhart-Harris said. After exposure to psilocybin, these receptors undergo a kind of “reset” that brings their activity back in line with what’s typical in a healthy brain, he theorizes.

“Action at the [serotonin] 2A receptor seems to be part of the picture of psilocybin’s mechanism of action,” although more research is needed to fully understand how the receptors and their associated brain regions change following exposure to the drug, Artin said.

In the meantime, to move psilocybin therapy for depression toward Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, large-scale clinical trials with hundreds of patients will need to be conducted, Daws said. (The largest trial to date included 233 patients.)

Carhart-Harris is also involved with ongoing research at Imperial College London to see if psilocybin therapy could benefit patients with other conditions, such as anorexia. In addition, at UCSF, Carhart-Harris is studying how the benefits of the psychedelic vary when the drug is paired with different forms of psychotherapy, or a lack thereof.

“I’m of the opinion that, really, the safety and efficacy rests on the drug being used with psychotherapy,” Carhart-Harris said. Assuming psilocybin therapy for depression is eventually approved, Carhart-Harris said that he might expect patients with treatment-resistant depression to have three to four dosing sessions in a year, in conjunction with psychotherapy similar to what they employed in their clinical trials.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese

Staff Writer

Nicoletta Lanese is a staff writer for Live Science covering health and medicine, along with an assortment of biology, animal, environment and climate stories. She holds degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her work has appeared in The Scientist Magazine, Science News, The San Jose Mercury News and Mongabay, among other outlets.

Source: Read Full Article