How many times have you watched a book adaptation on film or TV, and felt disappointed when a scene wasn’t quite how you’d pictured it? Or perhaps a character looked nothing like you’d imagined them to look?

Most people, when asked to form an image of a person they’re familiar with, can see it within their mind. In other words, it’s a visual, mental experience—similar to what we would see if the person were in front of us.

But it turns out that this isn’t true for everyone. Some people, when asked to form an image, will report they cannot “see” anything. This recently-identified variation of human experience was named in 2015 as aphantasia. It is estimated that 2% to 5% of the population have a lifelong inability to generate any images within their mind’s eye.

But, how do you recall details of an object or an event if you cannot actually see it in your mind? This is a question my colleagues and I sought to investigate in one of our recent studies.

Studying aphantasia

We assessed visual memory performance between individuals with aphantasia compared to those who had typical imagery.

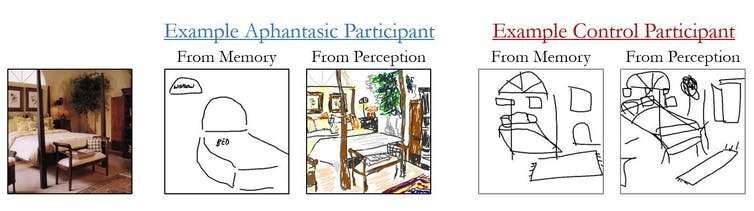

In the study, participants were shown three images of a living room, a kitchen and a bedroom, and were asked to draw each from memory. Their drawings were objectively reviewed by over 2,700 online scorers who assessed the object details (what objects looked like) and spatial details (the size and location of objects).

We expected people with aphantasia might find it difficult to draw an image from memory as they can’t summon these pictures in their mind’s eye.

Our findings showed people with aphantasia drew the objects of the correct size and location, but they provided less of the visual details such as color and also drew a fewer number of objects compared to typical imagers.

Some participants with aphantasia noted what the object was through language—such as writing the words “bed” or “chair”—rather than drawing the object. This suggests those with aphantasia could be using alternative strategies such as verbal representations rather than visual memory. These differences in object and spatial detail weren’t due to differences in artistic ability or drawing effort.

Our results suggested people with aphantasia have intact spatial imagery abilities—the ability to represent the size, location and position of objects in relation to each other. This finding has been reinforced in another of our studies examining how people with aphantasia perform in a number of imagery-related memory tasks.

We found people who lacked the ability to generate visual imagery performed just as well as people with typical imagery in these tasks. We also found similarities in performance within the classic mental rotation imagery task, in which people look at shapes to work out if they are the same shape rotated or different shapes.

This performance suggests that you don’t need to “see” with the mind’s eye to carry-out these tasks. On the other hand, it’s been documented that some people with aphantasia—but not all—are more likely to report difficulties with recognizing faces and also report a poor autobiographical memory—the memory of life events—a type of memory thought to rely heavily on visual imagery.

Life with aphantasia

People with aphantasia also describe other variations in their experience. Not everyone with aphantasia has a complete lack of imagery experience across all senses. Some might be able to hear a tune in their mind, but not be able to imagine visual images associated with it.

Similarly, research has shown that despite the inability to generate on-demand visual imagery, some people with aphantasia may still report experiencing visual imagery within dreams. Others say their dreams are non-visual—made up of conceptual or emotional content.

These fascinating variations illustrate some of the invisible differences that exist among us. Although many people with aphantasia may not be aware they experience the world differently, what we do know is people with aphantasia live full and professional lives. In fact, it’s been shown that people with aphantasia work within a range of both scientific and creative industries.

Source: Read Full Article