The search for youthfulness typically turns to lotions, supplements, serums and diets, but there may soon be a new option joining the fray. Rapamycin, a FDA-approved drug normally used to prevent organ rejection after transplant surgery, may also slow aging in human skin, according to a study from Drexel University College of Medicine researchers published in Geroscience.

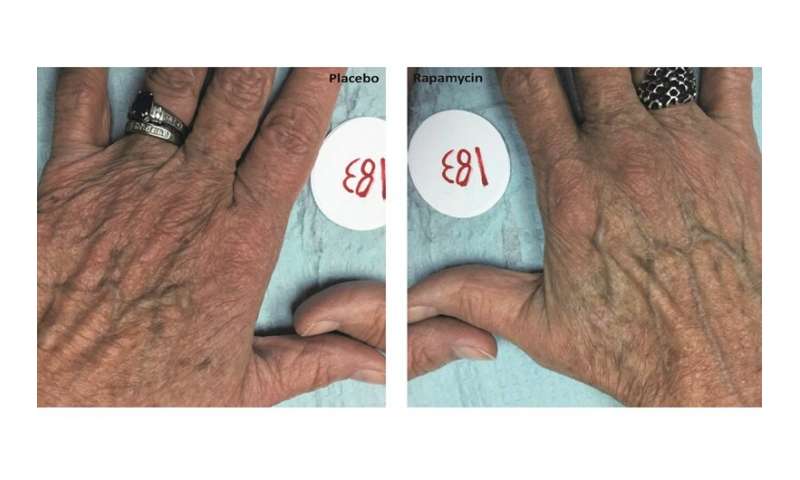

Basic science studies have previously used the drug to slow aging in mice, flies, and worms, but the current study is the first to show an effect on aging in human tissue, specifically skin—in which signs of aging were reduced. Changes include decreases in wrinkles, reduced sagging and more even skin tone—when delivered topically to humans.

“As researchers continue to seek out the elusive ‘fountain of youth’ and ways to live longer, we’re seeing growing potential for use of this drug,” said senior author Christian Sell, Ph.D., an associate professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the College of Medicine. “So, we said, let’s try skin. It’s a complex organism with immune, nerve cells, stem cells—you can learn a lot about the biology of a drug and the aging process by looking at skin.”

In the current Drexel-led study, 13 participants over age 40 applied rapamycin cream every 1-2 days to one hand and a placebo to the other hand for eight months. The researchers checked on subjects after two, four, six and eight months, including conducting a blood test and a biopsy at the six- or eight-month mark.

After eight months, the majority of the rapamycin hands showed increases in collagen protein, and statistically significant lower levels of p16 protein, a key marker of skin cell aging. Skin that has lower levels of p16 has fewer senescent cells, which are associated with skin wrinkles. Beyond cosmetic effects, higher levels of p16 can lead to dermal atrophy, a common condition in seniors, which is associated with fragile skin that tears easily, slow healing after cuts and increased risk of infection or complications after an injury.

So how does rapamycin work? Rapamycin blocks the appropriately named “target of rapamycin” (TOR), a protein that acts as a mediator in metabolism, growth and aging of human cells. The capability for rapamycin to improve human health beyond outward appearance is further illuminated when looking deeper at p16 protein, which is a stress response that human cells undergo when damaged, but is also a way of preventing cancer. When cells have a mutation that would have otherwise created a tumor, this response helps prevent the tumor by slowing the cell cycle process. Instead of creating a tumor, it contributes to the aging process.

“When cells age, they become detrimental and create inflammation,” said Sell. “That’s part of aging. These cells that have undergone stress are now pumping out inflammatory markers.”

In addition to its current use to prevent organ rejection, rapamycin is currently prescribed (in higher doses than used in the current study) for the rare lung disease lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and as an anti-cancer drug. The current Drexel study shows a second life for the drug in low doses, including new applications for studying rapamycin to increase human lifespan or improve human performance.

Rapamycin—first discovered in the 1970s in bacteria found in the soil of Easter Island—also reduces stress in the cell by attacking cancer-causing free radicals in the mitochondria.

In previous studies, the team used rapamycin in cell cultures, which reportedly improved cell function and slowed aging.

In 1996, a study in Cell of yeast cultures which used rapamycin to block TOR proteins in yeast, made the yeast cells smaller, but increased their lifespan.

“If you ramp the pathway down you get a smaller phenotype,” said Sell. “When you slow growth, you seem to extend lifespan and help the body repair itself—at least in mice. This is similar to what is seen in calorie restriction.”

The researchers note that, as this is early research, many more questions remain about how to harness this drug. Future studies will look at how to apply the drug in clinical settings, and find applications in other diseases. During the current study, the researchers confirmed that none of the rapamycin was absorbed in the bloodstream of participants.

Source: Read Full Article