The “Twincretin” era for treating patients with type 2 diabetes has begun, with the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) approval of tirzepatide for this indication on May 13, making it the first approved agent that works as a dual agonist for the two principal human incretins.

Tirzepatide represents “an important advance in the treatment of type 2 diabetes,” said the FDA’s Patrick Archdeacon, MD, associate director of the Division of Diabetes, Lipid Disorders, and Obesity, in a statement released by the agency.

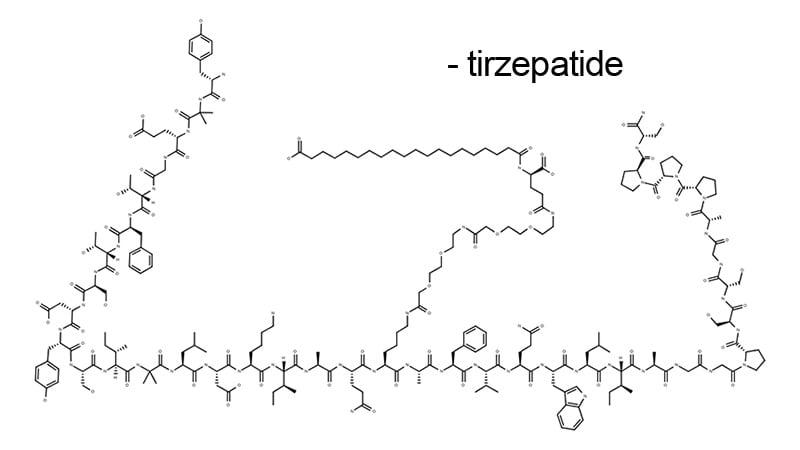

That advance is based on tirzepatide’s engineering, which gives it agonist properties for both the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor, as well as the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). Several agents are already approved for US use from the class with single-agonist activity on the GLP-1 receptor, including semaglutide (Ozempic for treating patients with type 2 diabetes; Wegovy for weight loss).

The FDA’s approved label includes all three dosages of tirzepatide that underwent testing in the pivotal trials: 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg, each delivered by subcutaneous injection once a week. Also approved was the 2.5 mg/week dose used when starting a patient on the agent. Gradual up-titration appears to minimize possible gastrointestinal adverse effects during initial tirzepatide use.

Tirzepatide, which will be marketed by Lilly as Mounjaro, will hit the US market with much anticipation, based on results from five pivotal trials, all reported during the past year or so, that established the drug’s unprecedented efficacy for reducing A1c levels as well as triggering significant weight loss in most patients with a generally benign safety profile.

“Impressive” Effects

The effects from tirzepatide on A1c and weight seen in these studies was “impressive, and will likely drive use of this agent,” commented Carol H. Wysham, MD, an endocrinologist at the MultiCare Rockwood Clinic in Spokane, Washington.

Tirzepatide received good notices in several editorials that accompanied the published reports of the pivotal trials. The first of these, a commentary from two UK-based endocrinologists, said that “tirzepatide appears to represent an advancement over current GLP-1 analogues, providing enhanced glycemic and weight benefits without an added penalty in terms of gastrointestinal adverse effects.”

The pivotal trials included head-to-head comparisons between tirzepatide and a 1.0-mg/week dose of semaglutide, as well as comparisons with each of two long-acting insulin analogs, insulin glargine (Lantus) and insulin degludec (Tresiba).

“These are the most important comparators,” Wysham said. “Tirzepatide was appropriately compared with the best-in-class and most effective glucose-lowering agents currently available,” said Ildiko Lingvay, MD, an endocrinologist and professor at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

“Given its outstanding efficacy at both lowering glucose and weight, I expect tirzepatide to have quick uptake among patients with diabetes,” Lingvay said. “The only limiting factor will be cost,” she added in an interview, highlighting the major stumbling block that could limit tirzepatide’s uptake.

“As with any new medication, access will be the biggest barrier to uptake,” agreed Alice Y.Y. Cheng, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Toronto.

Lingering Uncertainties

The timing of the comparison with semaglutide leaves some unanswered questions. The SURPASS-2 trial compared the three primary tirzepatide regimens (5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg/week) with a 1.0 mg/week dose of semaglutide, which was at the time the only approved dosage of semaglutide for patients with type 2 diabetes. Since then, a 2.0 mg/week dosage of semaglutide (Ozempic) received US approval for treating patients with type 2 diabetes, and a 2.4 mg/week dosage (Wegovy) received an FDA nod for treating people with obesity.

The lack of head-to-head data for tirzepatide against the 2.0 mg/week dose of semaglutide “leaves a clinical gap,” said Cheng. Tirzepatide “represents an advance over semaglutide at the 1 mg/week dose, but we do not know for sure compared to the higher dose.”

Another important limitation for tirzepatide right now is that the agent’s obligatory cardiovascular outcome trial, SURPASS CVOT, with about 12,500 enrolled patients, will not have findings out until about 2025, leaving uncertainty until then about tirzepatide’s cardiovascular effects.

“We are missing the cardiovascular outcome data — very important data will come” from that trial, noted Wysham. “There will be some reluctance to use the agent in high-risk patients until we see the results.”

Given tirzepatide’s proven efficacy so far, the missing cardiovascular results “are not a limitation for most patients, but for patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease I will continue to use agents with proven benefits until the SURPASS CVOT results come out,” Lingvay said.

And then there is the cost issue, something that Lilly had not yet publicly addressed at the time that the FDA announced its decision.

An analysis of cost effectiveness published by the US Institute for Clinical and Economic Review last February concluded that tirzepatide had a better impact on patient quality of life compared with 1.0 mg/week semaglutide for treating patients with type 2 diabetes, which gave it a modest pricing cushion compared with semaglutide of about $5500 per quality-adjusted life-year gained. But the researchers who prepared the report admitted that tirzepatide’s cost-effectiveness was hard to estimate without knowing the drug’s actual price.

Wysham has served as a consultant to Astra Zeneca, Abbott, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; she has been in the speakers bureau for Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; and she has received research funding from Abbott, Novo Nordisk, and Mylan.

Lingvay has received research grants paid to her institution from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Pfizer, and Mylan; she has been a scientific advisor or consultant to Novo Nordisk, Lilly, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Intercept, Intarcia, TARGET Pharma, MannKind, Valeritas, Merck, Bayer, and Zealand Pharma; and she received nonfinancial support from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and AstraZeneca.

Cheng has received personal fees from Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bausch, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Janssen, HLS Therapeutics, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

Mitchel L. Zoler is a reporter with Medscape and MDedge based in the Philadelphia region. @mitchelzoler

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and on Facebook.

You can also follow Medscape on Instagram, YouTube, and Linkedin.

Source: Read Full Article